Zoom Lens

1080p

Dopefish Family

PIR▲.MD

Tuesday, 10 November 2015

Monday, 9 November 2015

Hauntology: A Primer - The Absent Present Resonates (article)

The invention of genre names by journalists in order to describe new or emerging forms of music is a bugbear of most music fans. That these names are often taken up by the industry almost as soon as they are spoken and used to sort, categorise and even marginalise the creativity of those working at the cutting edge is perhaps one source of this animosity. The relationship between sellers of art and those whose business it is to talk about it form an articulated whole that for the most part does more to stifle artistic product than encourage it. Once the name takes hold and is heard echoing down the corridors of major labels it doesn’t take long for its function to move from the merely descriptive to the narrowly prescriptive, marking out the limitations of a newly established orthodoxy, losing its radical edge and becoming as rationalised and commodified as any other popular music. The music industry needs a constant stream of new names, new genres through which to maintain consumption, to re-ignite desire for the new, or perhaps simply to reform the old in a brighter sexier package.

So, it’s not surprising that the attention given in recent years by music journalists to the concept of hauntology has evoked as much ironic raising of eyebrows as it has serious discussion. In order the steer a path away from the predictable journalistic function much of this article will address the wider cultural and philosophical import of hauntology. My central theses and, what I hope to demonstrate with this primer is that there is a formal set of relations operating within the music of the artists below and, its influence and affect is something quite different from what has gone before. More than that, this formal set is one which (paradoxically, considering hauntology is mostly described as a genre) is not confined to one type or genre of music. In the final part of this article I will argue where I think this spectre, this ghost that is hauntology is heading next.

Popularised by critics such as Simon Reynolds and Mark "K-Punk" Fisher it has become synonymous with a group of artists working primarily in electronic music who demonstrate a curiously nostalgic and yet thoroughly modern approach to past musical and cultural forms. The Caretaker with his woozy re-appropriation of pre-war ballroom music, the Ghost Box label whose artists combine BBC radiophonic workshop style analogue electronics with 60s kitsch and public service broadcasts, and then there is Burial the secretive South Londoner whose records have become a touchstone for a uniquely mournful, yearning kind of urban music. What all these artists exhibit is an approach to the past which is other than a simple re-appropriation or pastiche. What hauntology is is a radically different relationship to that past, the lost opportunities of which still haunt us today as their unrealised potential. It is this paradoxical idea of a future that never came, of other possible worlds that may still be present, or maybe yet to come, which constitutes the central feature of those artists grouped under the name hauntology.

So, it’s not surprising that the attention given in recent years by music journalists to the concept of hauntology has evoked as much ironic raising of eyebrows as it has serious discussion. In order the steer a path away from the predictable journalistic function much of this article will address the wider cultural and philosophical import of hauntology. My central theses and, what I hope to demonstrate with this primer is that there is a formal set of relations operating within the music of the artists below and, its influence and affect is something quite different from what has gone before. More than that, this formal set is one which (paradoxically, considering hauntology is mostly described as a genre) is not confined to one type or genre of music. In the final part of this article I will argue where I think this spectre, this ghost that is hauntology is heading next.

Popularised by critics such as Simon Reynolds and Mark "K-Punk" Fisher it has become synonymous with a group of artists working primarily in electronic music who demonstrate a curiously nostalgic and yet thoroughly modern approach to past musical and cultural forms. The Caretaker with his woozy re-appropriation of pre-war ballroom music, the Ghost Box label whose artists combine BBC radiophonic workshop style analogue electronics with 60s kitsch and public service broadcasts, and then there is Burial the secretive South Londoner whose records have become a touchstone for a uniquely mournful, yearning kind of urban music. What all these artists exhibit is an approach to the past which is other than a simple re-appropriation or pastiche. What hauntology is is a radically different relationship to that past, the lost opportunities of which still haunt us today as their unrealised potential. It is this paradoxical idea of a future that never came, of other possible worlds that may still be present, or maybe yet to come, which constitutes the central feature of those artists grouped under the name hauntology.

Such a concept requires a departure from the usual understanding of presence and absence, being and non-being, which is why Derrida chose the play on words which is Hauntology; a combination of haunt (like a spirit or undead thing) and ontology, the philosophical study of what exists. Perhaps then in returning to music we can imagine that what these musicians are doing is a form of conjuration, a bringing forth of those lost moments, those unrealised potentials from our cultural past that have remained with us, haunting our present and emerging in these uncanny incantation of sound. If all this appears a little too academic or literary then hopefully the following review of some of the seminal works associated with hauntology may reveal both a more practical application along with its richness of thought.

One final point remains. It could be argued that this whole hauntology business is something of an instance of the emperors new clothes, that the nostalgic re-articulation of material from our musical past has been going on since the first attempts at tape splicing back in the 1950s. It is true indeed that those techniques first pioneered under the name musique concrete are still being deployed in their digital form by today’s electronic musicians, and that there has been a fairly constant interest in classic analogue sounds ever since the first analogue vs. digital debates erupted. Furthermore we could also point to works like Gavin Bryars The Sinking of the Titanic (1969), or William Basinski’s music utilising decaying tape loops to find that aspect of spectral re-imagining of the past which is associated with hauntology. I will concede this and certainly not deny that progenitors of hauntology are numerous. However, insofar as the artists below, grouped under the sign of hauntology represent a seemingly consistent set, each working from their own concerns, and yet demonstrating this core formal aspect towards both sound and, (for want of a better word) yearning towards the past, I think it appropriate to draw a line of demarcation and to begin the story of hauntology with the Caretaker’s debut album.

The Caretaker, aka Leyland Kirby of the now defunct VVM records deals in the type of hazy, dark ambient influenced music that wouldn’t sound out of place in a David Lynch film. His moniker and the name of his debut take their influence from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. His music recalls those somnambulistic drifts through the haunted hotel, the bizarre conversations with Mr Brady ("you are the caretaker, you’ve always been the caretaker"), and all that past horror hidden under the surface just beyond the sound of the band playing in the vast ballroom. This dread and portent pile up over almost seventy-five minutes of distorted 78s circa 1939, all filtered through a think electronic fog of drone, glitch and noise. The signifying effect is perhaps more of a slow burn than the other hauntologist but there is no denying the utterly uncanny sound on this debut. There is a raw unfettered quality to The Caretaker’s debut the heights of which he never quite matched again. Much of the strangeness of this music is achieved by the juxtaposition of barely treated vocal tracks such as Arthur Schwartz’ You and the Night and the Music next to slabs of atonal noise and claustrophobic drone pieces. Strung together in a manner that suggest as much of an attempt to shock as to haunt, the noise element of The Caretakers output would more or less vanish after this debut. The record contains many of the signature elements that have become associated with hauntological music including a penchant for vinyl like distortion and surface noise, the smudging and de-contextualisation of vocals, and a focus on layered almost desolate sounding acoustic space.

Five years later with Theoretically Pure Anterograde Amnesia; a mammoth 6CD set with no track titles we have moved to a preoccupation with memory, or more particularly the inability to create new memories. Mark Fisher in his sleeve notes for the set put it succinctly: "Let’s not imagine that this condition afflicts only a few unfortunates. Isn’t, in fact, theoretically pure anterograde amnesia the post-modern condition par excellence? The present - broken, desolate - is constantly erasing itself, leaving few traces." The record itself is a labyrinth of drawn out distortion and auditory artefacts, gone even are the rudimentary juxtapositions of noise, glitch and kitsch. Whatever spectre haunts this record its origins are unknown to us. Without bearings or even the ability to think an escape we find ourselves trapped in an endless present, the bad infinity. How did we get into this place? we can no longer remember. All that came before is endlessly recycled, circulated and the surplus extracted. Theoretically Pure Anterograde Amnesia is the sound of the ruinous shell that is left behind. The Caretaker marks the desolate borders around our current condition.

One final point remains. It could be argued that this whole hauntology business is something of an instance of the emperors new clothes, that the nostalgic re-articulation of material from our musical past has been going on since the first attempts at tape splicing back in the 1950s. It is true indeed that those techniques first pioneered under the name musique concrete are still being deployed in their digital form by today’s electronic musicians, and that there has been a fairly constant interest in classic analogue sounds ever since the first analogue vs. digital debates erupted. Furthermore we could also point to works like Gavin Bryars The Sinking of the Titanic (1969), or William Basinski’s music utilising decaying tape loops to find that aspect of spectral re-imagining of the past which is associated with hauntology. I will concede this and certainly not deny that progenitors of hauntology are numerous. However, insofar as the artists below, grouped under the sign of hauntology represent a seemingly consistent set, each working from their own concerns, and yet demonstrating this core formal aspect towards both sound and, (for want of a better word) yearning towards the past, I think it appropriate to draw a line of demarcation and to begin the story of hauntology with the Caretaker’s debut album.

The Caretaker, aka Leyland Kirby of the now defunct VVM records deals in the type of hazy, dark ambient influenced music that wouldn’t sound out of place in a David Lynch film. His moniker and the name of his debut take their influence from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. His music recalls those somnambulistic drifts through the haunted hotel, the bizarre conversations with Mr Brady ("you are the caretaker, you’ve always been the caretaker"), and all that past horror hidden under the surface just beyond the sound of the band playing in the vast ballroom. This dread and portent pile up over almost seventy-five minutes of distorted 78s circa 1939, all filtered through a think electronic fog of drone, glitch and noise. The signifying effect is perhaps more of a slow burn than the other hauntologist but there is no denying the utterly uncanny sound on this debut. There is a raw unfettered quality to The Caretaker’s debut the heights of which he never quite matched again. Much of the strangeness of this music is achieved by the juxtaposition of barely treated vocal tracks such as Arthur Schwartz’ You and the Night and the Music next to slabs of atonal noise and claustrophobic drone pieces. Strung together in a manner that suggest as much of an attempt to shock as to haunt, the noise element of The Caretakers output would more or less vanish after this debut. The record contains many of the signature elements that have become associated with hauntological music including a penchant for vinyl like distortion and surface noise, the smudging and de-contextualisation of vocals, and a focus on layered almost desolate sounding acoustic space.

Five years later with Theoretically Pure Anterograde Amnesia; a mammoth 6CD set with no track titles we have moved to a preoccupation with memory, or more particularly the inability to create new memories. Mark Fisher in his sleeve notes for the set put it succinctly: "Let’s not imagine that this condition afflicts only a few unfortunates. Isn’t, in fact, theoretically pure anterograde amnesia the post-modern condition par excellence? The present - broken, desolate - is constantly erasing itself, leaving few traces." The record itself is a labyrinth of drawn out distortion and auditory artefacts, gone even are the rudimentary juxtapositions of noise, glitch and kitsch. Whatever spectre haunts this record its origins are unknown to us. Without bearings or even the ability to think an escape we find ourselves trapped in an endless present, the bad infinity. How did we get into this place? we can no longer remember. All that came before is endlessly recycled, circulated and the surplus extracted. Theoretically Pure Anterograde Amnesia is the sound of the ruinous shell that is left behind. The Caretaker marks the desolate borders around our current condition.

Ghost Box Music has pretty much become the signature label of the mainstream understanding of hauntology. Their particularly English brand of queasy nostalgia and love of vintage electronics appeals as much to the Dr Who fan as to the more academic minded musicologist (although sometimes these are same people!). Founded by Julian House and Jim Jupp in 2004 they have quickly made a reputation for themselves with releases from The Focus Group, Belbury Poly, Eric Zann and The Advisory Circle. A Ghost Box release will typically contain samples from obscure 1960/70s TV shows, public service broadcasts or educational videos, library music, nods to the golden age of tape collage, and a rather large dose of surreal English wit. All this wrapped up in a consistently gorgeous design aesthetic that looks as if could have come through a portal direct from 1970 via Penguin books.

We are all Pan’s People by the Focus Group is a psychedelic trawl through dusty recordings of a skewed public event gone wrong, sounding somewhere between Jodorowsky’s Holy Mountain soundtrack and Delia Derbyshire on a bad LSD trip. As well as all this surreal humour and high kitsch there is also a feeling present on all Ghost Box records of loss, perhaps even melancholia. This feeling is especially acute on The Advisory Circle’s superlative Other Channels. Tracks like Mogodon Coffee Morning spice together banal pieces of incidental conversation, a fabulously trippy backing of phased lounge jazz and mournful strings over which flutters a pure sine wave melody. It’s melancholy to the extreme, conjuring images of long lonely days spent whiling away the time in the local greasy spoon, nameless faces coming and going, prospects limited, the coffee enough only to wake you up to another day in Thatcher’s Britain.

These songs could hardly be described as arriving through rose tinted spectacles, and indeed it would be a mistake to view records such as Other Channels or the recent Belbury Poly album From a Distant Star (breaking through to mainstream recognition with a positive review in the Guardian) as simply an orgy of kitsch, an exercise in purely retrograde nostalgia for the good old days before Dr Who got sexed up and the X-factor sausage factory began grinding away. In Jim Jupp’s words: "Like all the Ghost Box stuff, it’s an imaginary past. But given that, it’s from the late-70s of this imaginary past, if that makes sense?" (1)What we have here is that same distinction described in the introduction between reportage of the past and narritivising of a time that never took place. Or again with Jupp: "a nostalgia for nostalgia", a time when we could think beyond the confines of mass produced music towards the possibility of new sounds and new worlds. To put it another way: what Ghost Box and others like them articulate is not what is lacking in today’s cultural experience (authenticity, originality, genuine possibility away from the pressures of consumerism) but the lack of this lack; an inability even to imagine what it was the possibility of which went away during the epochal shifts in political and economic reality in the period 1970-1990. The other world that the mock TV broadcasts of Ghost Box Music seem to soundtrack is one which has no linear path from its time to ours. As Jupp said, his 1970s never happened and therefore the present, the point from which he is articulating this nostalgia is also one which has yet to come. If hauntology refers to any world other than our own it is precisely this absent present that is yearned for in the reconfiguring of a past where other futures were yet to be foreclosed.

http://www.nightoftheworld.com/writingfiles/hauntprimer.html

We are all Pan’s People by the Focus Group is a psychedelic trawl through dusty recordings of a skewed public event gone wrong, sounding somewhere between Jodorowsky’s Holy Mountain soundtrack and Delia Derbyshire on a bad LSD trip. As well as all this surreal humour and high kitsch there is also a feeling present on all Ghost Box records of loss, perhaps even melancholia. This feeling is especially acute on The Advisory Circle’s superlative Other Channels. Tracks like Mogodon Coffee Morning spice together banal pieces of incidental conversation, a fabulously trippy backing of phased lounge jazz and mournful strings over which flutters a pure sine wave melody. It’s melancholy to the extreme, conjuring images of long lonely days spent whiling away the time in the local greasy spoon, nameless faces coming and going, prospects limited, the coffee enough only to wake you up to another day in Thatcher’s Britain.

These songs could hardly be described as arriving through rose tinted spectacles, and indeed it would be a mistake to view records such as Other Channels or the recent Belbury Poly album From a Distant Star (breaking through to mainstream recognition with a positive review in the Guardian) as simply an orgy of kitsch, an exercise in purely retrograde nostalgia for the good old days before Dr Who got sexed up and the X-factor sausage factory began grinding away. In Jim Jupp’s words: "Like all the Ghost Box stuff, it’s an imaginary past. But given that, it’s from the late-70s of this imaginary past, if that makes sense?" (1)What we have here is that same distinction described in the introduction between reportage of the past and narritivising of a time that never took place. Or again with Jupp: "a nostalgia for nostalgia", a time when we could think beyond the confines of mass produced music towards the possibility of new sounds and new worlds. To put it another way: what Ghost Box and others like them articulate is not what is lacking in today’s cultural experience (authenticity, originality, genuine possibility away from the pressures of consumerism) but the lack of this lack; an inability even to imagine what it was the possibility of which went away during the epochal shifts in political and economic reality in the period 1970-1990. The other world that the mock TV broadcasts of Ghost Box Music seem to soundtrack is one which has no linear path from its time to ours. As Jupp said, his 1970s never happened and therefore the present, the point from which he is articulating this nostalgia is also one which has yet to come. If hauntology refers to any world other than our own it is precisely this absent present that is yearned for in the reconfiguring of a past where other futures were yet to be foreclosed.

http://www.nightoftheworld.com/writingfiles/hauntprimer.html

Lo-Fi Electronic Music Aesthetic

Outsider House

Characterised by is use of analogue production methods, using synthesisers and tape machines instead of producing it digitally. 'The resulting music is often rough-sounding and "lo-fi", in contrast to the "polished cleanliness" of other contemporary electronic music genres'.

Hessle Audio's Ben UFO first playfully coined the term "outsider house" during a Rinse FM show, in reference to the outsider art phenomenon that champions untrained, "naive" artists from beyond the art world. Before long, it was being applied to any American producers whose tracks sounded like they'd been recorded backwards on a reel-to-reel recorder using sandpaper instead of tape. (wikipedia)

Below are some artists and record labels that champion the sound and have added links to listen.

Note: Many artists now reject the term outsider house as they don't want to associate

L.I.E.S (Long Island Electrical Systems)

LIES is a Brooklyn record label that releases music that can be categorised as 'Outsider House'. The aesthetic of the label follows the lo-fi production of the music, using risograph printing, photo copy and collage to create much of its artwork (artwork/design by More More Now). The DIY aesthetic is reminiscent of the punk movement which started as a reaction to the neat/uptight establishment of the generation before it. This theme can be seen in Outsider House which was possibly at first a subconscious reaction from the music producers trying to find an alternative new sound to the structured and polished sounds of mainstream electronic dance music.

You might have expected [the growth of the internet] to make labels—whose role it usually is to organise the discovery, representation, manufacturing and distribution of their artists’ music—redundant in the modern era. And as a result, you might have expected music producers and their listeners alike to be reduced to an atomised population of lone computer-clickers. But curiously, labels are flourishing, and they form key nodes in a new form of DIY musical culture that is as sociable as ever.

feel like the existence of physical items is important in preserving our own attached memories to such listening experiences, yet sometimes I feel like it’s impractical in an ecological sense and is slowly growing less acceptable for the shifting musical listening trends.” Then, elegantly and poignantly echoing Zoom Lens’s sonic and visual aesthetic: “We are in constant conflict in losing the physical things that bring us a sense of connection, yet we enjoy the ease of instant gratification.” Ailanthus’s Michael confesses, “I always wonder where these files will be in decades, like what if kids go to thrift stores and rummage old external hard drives for rare internet music.”

Characterised by is use of analogue production methods, using synthesisers and tape machines instead of producing it digitally. 'The resulting music is often rough-sounding and "lo-fi", in contrast to the "polished cleanliness" of other contemporary electronic music genres'.

Hessle Audio's Ben UFO first playfully coined the term "outsider house" during a Rinse FM show, in reference to the outsider art phenomenon that champions untrained, "naive" artists from beyond the art world. Before long, it was being applied to any American producers whose tracks sounded like they'd been recorded backwards on a reel-to-reel recorder using sandpaper instead of tape. (wikipedia)

Below are some artists and record labels that champion the sound and have added links to listen.

Note: Many artists now reject the term outsider house as they don't want to associate

L.I.E.S (Long Island Electrical Systems)

LIES is a Brooklyn record label that releases music that can be categorised as 'Outsider House'. The aesthetic of the label follows the lo-fi production of the music, using risograph printing, photo copy and collage to create much of its artwork (artwork/design by More More Now). The DIY aesthetic is reminiscent of the punk movement which started as a reaction to the neat/uptight establishment of the generation before it. This theme can be seen in Outsider House which was possibly at first a subconscious reaction from the music producers trying to find an alternative new sound to the structured and polished sounds of mainstream electronic dance music.

Ron Morelli

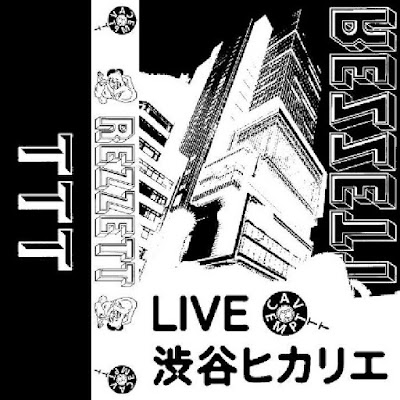

Rezzett

Opal Tapes

Lobster Theremin

feel like the existence of physical items is important in preserving our own attached memories to such listening experiences, yet sometimes I feel like it’s impractical in an ecological sense and is slowly growing less acceptable for the shifting musical listening trends.” Then, elegantly and poignantly echoing Zoom Lens’s sonic and visual aesthetic: “We are in constant conflict in losing the physical things that bring us a sense of connection, yet we enjoy the ease of instant gratification.” Ailanthus’s Michael confesses, “I always wonder where these files will be in decades, like what if kids go to thrift stores and rummage old external hard drives for rare internet music.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)